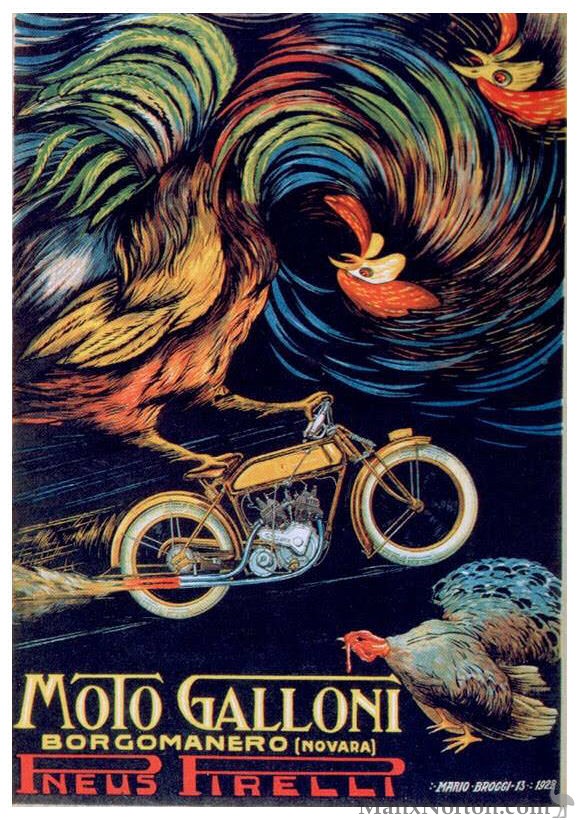

Race, blood, and soil meant little to the adolescent Oskar. He was one of those boys for whom a motorcycle is the most compelling model of the universe. And his father — a mechanic by temperament — seems to have encouraged the boy's zeal for red-hot machinery. In the last year of high school, Oskar was riding around Zwittau on a red 500cc Galloni. A school friend, Erwin Tragatsch, watched with unspeakable desire as the red Galloni farted its way down the streets of the town and arrested the attention of promenaders on the square. Like the Kantor boys, it too was a prodigy — not only the sole Galloni in Zwittau, not only the only 500cc Italian Galloni in Moravia, but probably a unique machine in all Czechoslovakia.

In the spring of 1928, the last months of Oskar's adolescence and prelude to a summer in which he would fall in love and decide to marry, he appeared in the town square on a 250cc Moto-Guzzi, of which there were only four others on the Continent outside Italy, and those four owned by international racers—Giessler, Hans Winkler, the Hungarian Joo and the Pole Kolaczkowski. There must have been townspeople who shook their heads and said that Herr Schindler was spoiling the boy.

But it would be Oskar's sweetest and most innocent summer. An apolitical boy in a skullfitting leather helmet revving the motor of the Moto-Guzzi, racing against the local factory teams in the mountains of Moravia, son of a family for whom the height of political sophistication was to burn a candle for Franz Josef. Just around the pine-clad curve, an ambiguous marriage, an economic slump, seventeen years of fatal politics. But on the rider's face no knowledge, just the wind-flattened grimace of a high-speed biker who—because he is new, because he is no pro, because all his records are as yet unset— can afford the price better than the older ones, the pros, the racers with times to beat.

His first contest was in May, the mountain race between Brno and Sobeslav. It was highclass competition, so that at least the expensive toy prosperous Herr Hans Schindler had given his son was not rusting in a garage. He came in third on his red Moto-Guzzi, behind two Terrots which had been souped up with English Blackburne motors. For his next challenge he moved farther from home to the Altvater circuit, in the hills on the Saxon border. The German 250cc champion Walfried Winkler was there for the race, and his veteran rival Kurt Henkelmann, on a water-cooled DKW. All the Saxon hotshots—Horowitz, Kocher, and Kliwar—had entered; the Terrot- Blackburnes were back and some Coventry Eagles. There were three Moto-Guzzis, including Oskar Schindler's, as well as the big guns from the 350cc class and a BMW 500cc team. It was nearly Oskar's best, most unalloyed day. He kept within touch of the leaders during the first laps and watched to see what might happen. After an hour, Winkler, Henkelmann, and Oskar had left the Saxons behind, and the other Moto-Guzzis fell away with some mechanical flaw. In what Oskar believed was the second-to-last lap he passed Winkler and must have felt, as palpably as the tar itself and the blur of pines, his imminent career as a factory-team rider, and the travel-obsessed life it would permit him to lead.

In what then he assumed was the last lap, Oskar passed Henkelmann and both the DKW'S, crossed the line and slowed. There must have been some deceptive sign from officials, because the crowd also believed the race was over. By the time Oskar knew it wasn't — that he had made some amateur mistake — Walfried Winkler and Mita Vychodil had passed him, and even the exhausted Henkelmann was able to nudge him out of third place.

He was feted home. Except for a technicality, he'd beaten Europe's best.

Tragatsch surmised that the reasons Oskar's career as a motorcycle racer ended there were economic. It was a fair guess. For that summer, after a courtship of only six weeks, he hurried into marriage with a farmer's daughter, and so fell out of favor with his father, who happened also to be his employer.

Extract from Chapter 1 of Schindler's Ark by Thomas Keneally

Serpentine Publishing Co. Pty Ltd. 1982

N.B. This text was extraced from a pdf at https://stcre.weebly.com/uploads/2/6/4/1/26417597/1982-thomas-keneally-schindlers-ark.pdf. It is not a perfect version as most of the non-ascii symbols - umlauts and the like - have been replaced with @.