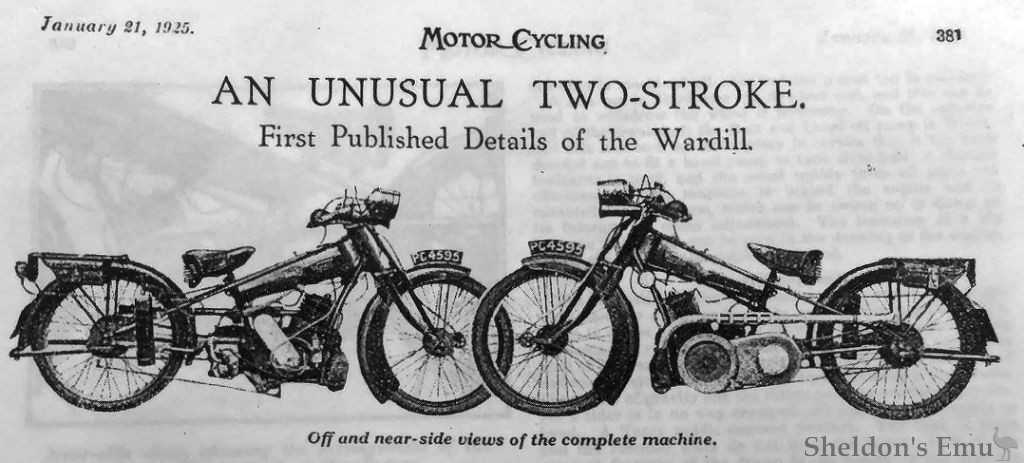

IT was over a year ago when we saw the first Wardill, and since then we have from time to time observed one or two of them on the road, either in trials or being ridden in the ordinary course of business. When, during the Exeter trial, we were invited to share a secret we accepted the invitation to view the machine as soon as possible. The general lay-out and appearance of the machine incorporate numerous features which are novelties of design. The engine, which is protected by several patents, is of a type new to motorcycle design, and is described as a pump-charged two-stroke.

No crankcase compression is used and the makers claim a largely increased life for the bearings on account of there being no fuel in the crankcase to contaminate the lubricating oil. The ingenious layout of the engine is made clear in the arrangement of the drawing. The cast-iron working piston is of the conventional deflector type. The charger piston takes the form of a very wide ring surrounding the main piston and working in a separate bore of the cylinder.

The position of the engine in the frame and the method of clipping the silencer direct on to the engine are made clear in this drawing.

How the Charger Piston is Operated.

The crankshaft, which is a stiff nickel-steel forging, has, besides the crank throw, two eccentrics formed on it, and these eccentrics drive the charger piston through the agency of two short connecting rods. The crankpin and eccentrics centres are nearly opposite each other, so that when the working piston ascends the charger piston is descending.

If, for a moment, we ignore the timing lag given to the charger, the cycle of operations can be followed.

In the drawing the main piston is shown at top dead centre, and if we imagine that the engine is working, the piston is at the firing point. The charger piston is uncovering the inlet port, and owing to the vacuum existing in the space above it, gas is rushing in from the carburetter.

Note the charger piston working in a separate bore of the cylinder.

A sectional view. Note the charger piston working in a separate bore of the cylinder.

The working piston descends, and as it nears the bottom of the stroke it uncovers first the exhaust port and then the transfer port. While it is doing this the charger piston is ascending and compressing the gas; and when the transfer port is opened by the main piston the gas from the charger cylinder rushes into the working cylinder in the conventional manner and the cycle of operations proceeds as in an ordinary two stroke engine. As designed, however, the two cranks are not set directly at 180 degrees and the charger piston is given a slight lag.

The reason for this is that by forcing the gas into the cylinder after the working piston has passed bottom dead centre the inventors reduce to a minimum the losses of inlet gas into the exhaust pipe. Some experiments performed on the same engine - first, fitted with the piston positions at 180 degrees to each other, and then with a piston given a 38 degrees lag, showed that the latter arrangement gave more power and improved fuel consumption.

The volume swept by the working piston is 346 c.c. (73 mm. by 83 mm.), but the charger cylinder capacity is 417 c.c.., so that the main cylinder and most of the combustion chamber is filled with clean gas and thoroughly scavenged. On a conventional two stroke the cylinder can never be more than about 80 per cent. full and the combustion chamber cannot be swept. Even the four-stroke. engine never has its combustion head charged unless the engine is fitted with a supercharger.

It is suggested by the inventors of the Wardill that, besides giving a greatly increased power output, their origin is more flexible than any ordinary two-stroke possibly can be.

Carefully Manufactured.

Mechanically the idea has been well carried our, and the unit is both sturdy and accessible. The cylinder possesses thick walls and is well ribbed, and the detachable head is spigoted to the cylinder and held in place by four screws. The ports are all bridged, and a ribbed manifold leads the exhaust gas to the large aluminium silencer. In less than 10 minutes both cylinder and head can be removed. Cast-iron pistons are used, but the makers have by no means abandoned their experiments with aluminium.

Two wide rings are fitted to the working piston, but the charger piston has only a single narrow ring, as the pressure in its cylinder is never very high. The gudgeon pins, which are hollow and of 11/16 in. diameter, are a push fit in the piston and are prevented from scoring the cylinder walls by aluminium end pads. The crankshaft is a solid nickel-steel...

.........end of page