(L.) The change speed lever is carried through the tank, leaving the sides quite smooth. Glass-topped filler taps are used.

(R.) Provision for adjustment of the rear chain on the Rover is by the draw bolts and serrated washers shown.

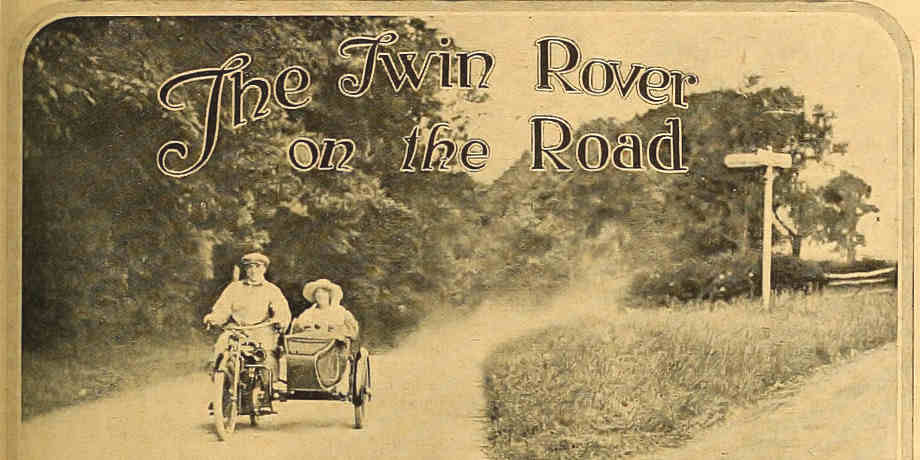

SOME motor cycles are so well and conveniently arranged in the matter of their controls that one may mount them and at once ride away with a feeling of familiarity. Such a mount is the Rover, the latest twin-cylinder specimen of which we lately had the pleasure of testing on the road. The 5-6 h.p. twin Rover-Jap is a wartime creation - it was originally produced to satisfy war demands, and right well it acquitted itself. Now that examples of the machine are available for private riders, it is, perhaps, not surprising, in view of the times in which we live, to learn that the order list is extremely lengthy. The machine to which we refer possesses no claim to novelty or even originality; it is the embodiment of well tried practice in motor cycle design, and to many makes a particularly strong appeal on that account. We tested the Rover with the standard sidecar attachment and a ten stone passenger. From the first starting was an extremely simple matter; no surprise in that, perhaps, for we had already learned to respect the care with which Rover' products are examined and tested before issue from the works. Away we went through Warwick and Barford to our favourite testing ground - the Edge Hill range.

Keeping up a lively pace through the Kineton straight to the foot of Edge, we at once opened out and swept round the bend at a crackling pace. The second gear of 9 to 1 sufficed until well round the second bend, when a drop to low (17 to 1) was necessary on the 1 in 6 stretch. But on this ratio the engine naturally raced away and had to be throttled down; it was abundantly clear that with a slightly lower ratio for the middle gear, the lowest gear would never have been requisitioned. A second ascent confirmed this opinion.

Observant readers well know that a favourite test of ours is stopping and restarting in the middle of a steep Kill. It brings to light many things - good or bad - about a motor cycle. First, the brakes have to he first rate to hold the machine on the gradient; secondly, the engine must be properly adjusted and controllable; and thirdly, the clutch must be of such a material and of such dimensions that it is well capable of starting the not inconsiderable sidecar load on single figure gradient.

This new 1919 Rover answered every one of those requirements; we repeated the operation three times "just to make sure," and on each occasion the machine performed consistently well.

Double purpose twins are not as numerous as they might be. Manufacturers who favour sidecar attachments seem gradually to drift toward an 8 h.p. mount of a luxurious type fitted only for passenger work. In the case of a twin of the Rover type - whose J. A. P. engine of 70 x 85 mm. bore and stroke has a capacity of 654 c.c. - the machine is highly suitable and equally attractive to many as a solo or sidecar machine, for it is of medium weight as chain-driven three-speeders go, and consequently not a burden to handle. Smoothness of running is one of its virtues, and the silent running J. A. P. largely contributed to this happy state of affairs, for its valve gear was noticeably quiet. The gear box is exceptionally sturdy and apparently well up to its work, whilst the chain cases are a sound job and devoid of rattle. Our trip was purely a run of pleasure, for no untoward incident occurred, the Rover responding to every call. Toward the conclusion of the run one noticed a scraping sound when bounding over the pot-holes due to the new chain having stretched and fouling the casing.

This experience only served to bring home the handiness of the special chain adjustment provided, which soon set matters right. The device, which deserves to be better known, is illustrated. First the spindle nuts are loosened and then the draw bolts used to tension the chain correctly. The serrated washers are then placed in corresponding positions on the pegs on each side of the fork end to ensure the wheel remaining central with the frame, thus taking all strain off the chain adjusters themselves.

The Motor Cycle August 14th, 1919.