1913 A V-twin was added, along with Fafnir singles.

1914 They added Villiers and MAG engines.

1916 The range had been cut to two models. One used the 2½ hp JAP engine and the other a 2.75.hp Peco. Both had two speeds, chain drive and sprung forks. The war intensified, and motorcycle production ceased.

By reason of the design of the Edmund spring frame, it readily adapts itself to an attractive looking sporting mount, as is shown in this new Barr and Stroud engined model, which is used for demonstration purposes outside the Kelvin Hall.

1920 The marque reappeared with two models. One had a 293cc JAP engine, two-speed Burman gearbox and chain-cum-belt drive. The other had a 293cc Union two-stroke engine and Enfield two-speed all-chain transmission. Both still used the patent spring frame.

1921 The two-stroke was dropped and the JAP was joined by a 348cc sv Blackburne.

1922 The two models from the previous year were now fitted with 545cc Blackburne and 348cc sleeve-valve Barr and Stroud engines. The larger was only built for that year.

1923 Other models continued and there was also the 348cc Blackburne. During that year the company suffered financial collapse, but it was quickly reformed to carry on using the same JAP, Blackburne, and Barr and Stroud engines. They continued in this vein for the next few years.

1926 By that year only the 348cc sv and ohv Blackburne engines were utilised. It was to be their last year.

A few days ago we were able to test the Douglas-engined spring frame Edmund illustrated in The Motor Cycle of July 9th. The combination of the smooth running horizontally-opposed engine in conjunction with the clever frame design rendered the machine one of the most comfortable we have ever ridden. The machine was driven at a smart pace over a very bumpy stretch of road, but the leaf springs and coil shock absorbers reduced even the worst bumps to such a degree that no jar of any sort was felt, but only an easy undulating motion.

The Motor Cycle, August 6th, 1914

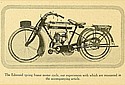

The Edmund spring frame motor cycle, our experiences with which are recounted in the accompanying article.

2½ h.p. Spring Frame Edmund-Jap

Bore and Stroke 70 x 76 mm.. Cubic Capacity 292 c.c. ; Enfield Two-speed Gear and Transmission.

WE recently, had the opportunity of putting a machine of the above make to a somewhat extensive test, and since our riding was done over roads which considerably varied in hilliness and quality, we are now able to speak with practical knowledge concerning this interesting lightweight.

The machine is of special interest on account of its springing, and since almost any make of lightweight engine can be adapted to the Edmund spring frame, our interests were centred more on the efficiency of the springing system than on the capabilities of the 2½ h.p. J. A. P. engine, the merits of which are sufficiently well known. In these days of bad roads any adequate system of rear springing for lightweight machines is of special interest to many of our readers, and it cannot be doubted that in due course rear spring frames will become the common order.

Description of the Springing.

Though we have already described the Edmund springing system, a brief outline as to its working points is here necessary. The weight of the rider is supported by two long leaf springs extending from under the saddle to the rear carrier stays. The tension of these springs can be adjusted to suit one's weight by raising or lowering the bolts that support their thin ends, and for this purpose the stays are flattened and several holes are drilled to give the various settings. Short coil springs, which act as shock absorbers, are fitted to the lower ends of the stays.

The top bar, which is pivoted at the ; steering head, moves vertically with the saddle, and the footrests are attached to the extended saddle pillar which passes through the seat tube. Thus it will be seen that the saddle and the footrests move in unison against the tension of the long leaf springs, which insulate the rider from road shock and engine vibration, the portion of the frame which carries the engine and the road wheels being rigid.

The tank is attached to the top bar, and, since this member is sprung while the engine is unsprung, petrol land oil are conveyed from their respective tanks by flexible petrol-proof rubber tubing as used by the British and French Governments on flying machines. The originality of the frame design also necessitates a divided tank, one compartment of which carries one quart of oil and half a gallon of petrol, while the other carries one gallon of spirit. The convenience of possessing two tanks is fully realised in practical use, though the compartments can be interconnected if desired.

The Comfort Provided.

Extreme simplicity of design is a great point in favour of the Edmund springing system, the few unconventional features involved being obvious at a glance. Many of the roads we negotiated would be hard to equal for their rapid succession of pot-holes, and during the year we have ridden many machines, from the big touring twin down to the two-stroke lightweight, over these same roads. There is no question, however, that the machine under review has proved by far the most comfortable we have handled amidst such conditions, the action of the long springs being so gradual that only the worst of pot-holes conveyed anything resembling a jolt to the rider. Probably the chief point in favour of this system of springing is its absence of sudden recoil when negotiating pot-holes in rapid succession. There is no tendency for the rider to bounce up and down with increasing violence when travelling at speed the action of the springs being at all times slow and steady - a point we emphasise for the benefit of those who have had no experience with rear sprung frames. Some such arrangement is obviously in demand during this period . when lightweights are so much used about our military centres, where the roads are generally of the worst.

The carrier is partly sprung, and is more comfortable than the rigid type for pillion riding, but it would add to the general satisfaction of the machine for present-day demands if this portion were sprung with the saddle — an embodiment somewhat difficult to attain.

Engine and General Efficiency.

The 2½ h.p. J. A. P. engine displayed a surprising kick and vigour when opened up to normal speed, and we found the machine slightly faster than most two-strokes we have handled of the same power. The marvellous economy of this little mount is, however, its most surprising feature, the re-filling of the petrol tank being such an occasional event that one is apt to forget it as a practical necessity. The machine is fitted with Amac carburetter and Dixie magneto.

Its hill-climbing capabilities are all that can be desired for normal work. The Enfield gear and transmission is delightful in action, the machine picking up from a standing start on quite a steep gradient. In no way, therefore, would this little mount fall short of meeting the demands of the ordinary pleasure rider, and yet it is by no means heavy.

There are, however, one or two insignificant points where improvement might possibly be made. The fixed ignition prevents one from obtaining the best out of the engine, and does not improve matters when starting from cold. Like almost every light-weight we have handled this season the footrests are too near the ground. On these little machines, with their safe riding position, one gets into the way of leaning the machine at a considerable angle when negotiating right angle bends, and if the road surface is irregular one is apt to foul the footrests with considerable force during moments of forgetfulness. We would also like to see the chain guards of lightweight machines made of more solid material, so that these members are not so susceptible to injury and the resultant rattle.

The Motor Cycle, October 14th, 1915. Page 366

EDMUND. (Stand 138.)

Super Suspension for the Rider.

2 ¾ h.p. Model

71x88 mm. (348 c.c.); single-cyl. four-stroke; side valves; drip feed lubrication; Amac carb.; chain-driven mag,; 3-speed gear; clutch and kick-starter; chain drive 26x2 ¼in. tyres. Price: Solo, £78 15s.; with Sidecar, £97 5s.

C. E. Edmund and Co. (1920), Ltd., Milton Works, Milton Street, Chester.

Edmund machines are, of course, famous as pioneers in the movement to provide increased comfort for the rider. The forced alteration of the oil filler to a more convenient pattern. The weight of the three-speed model is still well under 180 lb., the two-speed model being proportionately lighter The sports model is fitted with a close ratio gear box. The engine of the latest machine is a development of the 1922 type of racing unit.

The machines have been manufactured substantially in their present form for many years past. For 1923 three models are offered, namely, touring, sports, and super-sports, all of which are normally fitted with Blackburne engines overhead valves being utilised on the super-sports type.

Options consist of a Barr & Stroud engine on the touring model, or a special J.A.P. engine on the sports model. The policy of the firm is to offer 350 c.c. machines of the best quality, distinguished by the comfort bestowed by the patent frame. Several minor alterations of interest are to be noticed. The cast aluminium chain guards are exceptionally neat. Customers may choose either a sprung or rigid carrier.

A large armoured toolbag is fitted to the tourist model. The sports model carries its expansion box in the modern fashionable position level with the rear wheel ; this box is of excellent pattern, being of rectangular shape made in cast aluminium and very heavily ribbed in order to cool the gasses as far as possible.

Olympia Show 1922

The Motor Cycle, November 30th, 1922. Page 842

Sources: Graces Guide, The Motor Cycle