A Review of the Motor Cycle Exhibits at the Paris Automobile Show. Tendencies in Design. Many British Machines. An International Aspect.

The Paris Automobile Show at the Grand Palais, Champs Elysées, was opened on Tuesday of last week. Without doubt, it is the most magnificent display of the productions of the motor cycle, cycle, and car industries of France (together with representative exhibits of Great Britain, the United States of America, Belgium, and Italy), - that has ever been shown at any of the Paris exhibitions, which have been held for sixteen years.

At this time, when we are reviewing the French built motor cycles, we can opportunely refer briefly to the French motor cycle industry. When a glorious British win is recorded on the Continent we are apt to pat ourselves on the back, and think how wonderfully superior British motor cycles are to those made in other countries. Our products are certainly excellent now, but they were not always so. Years ago, when practically every English motor cycle had a French or Belgian engine, France led the way.

The Past.

In those days the names of De Dion and Werner meant perfection among motor cycle engines. Races without number were won by the brothers Collier, then daring youths, who drove their 2 3/4 h.p. De Dion engined Matchlesses to victory on Canning Town track. That was a wonderful little engine, most reliable, and though, compared with a modern motor, it seemed a mass of metal, it was a marvel for cool running and efficiency.

Curiously enough the De Dion-engined motor bicycle was a rarity in France, though this is, perhaps, not to be wondered at, as the makers' motor tricycle catalogue of those days stated that they were prepared to accept orders for motor bicycles hut did not recommend them.

At that time French motor bicycles and their riders were unassailable in their own country. Undoubtedly we owe much to our French friends for their brilliant pioneer work in the days of long ago.

The Present.

Pulley side of the two-cylinder two-stroke engine-gear unit of the new model Bleriot.

More on Bleriot

At the present moment the French motor cycle industry, like every other, is in a bad way, owing to trade depression, but the French motor cycle movement is on the increase. The reasons for this are interesting. First, the wonderful success of the motor cycle in England has caused the Frenchman to think there must be something in it; secondly, during the late war, he has seen with his own eyes what our machines can do; and, lastly, the end of the war has thrown a number of British and American ex-army motor cycles on the market at a very moderate figure. This was naturally somewhat of a blow to the French motor cycle trade, but was good for the movement as a whole.

The Future.

It is a little difficult for the foreign observer to foretell the future in a country other than his own, but it is the opinion of those who know France well that there is a distinctly good prospect for the cheap motor bicycle; but it must be cheap, as the young Frenchman is not so well off as the average English youth. It may be light, but it must be robust, because the French roads, especially in and near the great towns, are more bumpy than our own. Owing to the low cost of upkeep there must be a greater demand for the motor cycle at the present time when few can afford a car, but much depends on the roads, and, unless they are put into a good state of repair, and are well maintained, the future of the motor cycle in France cannot be too rosy.

The beautiful, long, straight French roads are much improved since last year, but more work on them is needed, while the great main thoroughfares need building of Tarmac or other hard wearing material. Provided the exchange is stabilised between the two countries, and the rate is brought down more nearly to the normal, there is hope for British machines to be sold in France. Their quality is much appreciated and fully recognised, as some thousands are in use at the present day. Many French machines are now built on British lines, but while the fact that this must be so is realised, it is evident that a good deal of work yet remains to begone to bring them even to a state" of equality with our own productions.

Motor Cycles at the Paris Salon

OCTOBER 13th, 1921. P.444

TENDENCIES IN FRENCH DESIGN.

Unconventionality In Engine Design and Frame Construction. Side by-side Twin Engines Favoured. Many Motor-assisted Bicycles.

ALTHOUGH the French motor cycle industry is as old as, if not older than, that of this country, in order to be fair to our friends across the Channel one has to remember that the motor cycle movement in France was practically moribund in 1914. When the re-establishment of peace time industries took place in 1919, the French motor cycle industry was to all intents and purposes reborn.

Viewed as the productions of a new industry, the French motor cycles at the Paris Show reveal an enthusiasm and enterprise which, from the British standpoint, is surprising, to say the least. The English visitor must be astonished at some of the remarkable designs which are so different from what the British rider expects. But it does not necessarily follow that the British idea is right, at least so far as France is concerned. If the French ideal is a machine totally opposite to the British, then several manufacturers have achieved their aim. If, on the other hand, the potential French rider prefers a machine on British or American lines, then the makers referred to are in the same position as their confreres of two decades ago. They are pioneers - a much to be praised body of enthusiasts who, unfortunately perhaps, seldom reap any benefit from their labours and ingenuity.

Three Main Classes.

The Lutece, which has a side-by-side twin engine (built integral with gear box), shaft drive, and car type springing.

More on Lutece

The French motor cycles exhibited at the Grand Palais may be divided into three main classes : (1.) The unconventional. (2.) The conventional. (3.) The motorised bicycle.

Conventionality is generally a matter of viewpoint. What is conventional in England may be unconventional in France; but in this case the use of the terms is quite permissible, for the reason that the unconventional designs are different from any yet produced by any country. Therefore they are as unconventional to French buyers as they would be to the British. The very English expression " like nothing on earth " was never better exemplified than in several machines at the Salon, but this is not meant in any sarcastic spirit; indeed, to apply the phrase to any design is, at any rate, a tribute to its originality.

We may, therefore, summarise the first group of French motor cycles as being extremely original, although they will depend for their future success upon two main factors - first, their originality, which must be proved justifiable by demonstration of some great advantage, whether in cost, economy, or increased comfort; and, secondly, upon whether their unique appearance will be accepted by the buying public.

Now, nine-tenths of British makers appreciate that unconventionality creates a line of resistance difficult to overcome, therefore they avoid it, and one is sometimes inclined to agree with their policy. On the other hand, if there were no brave spirits willing to face all criticism by launching ,out on new lines, there would be no advancement. In England, at all events, it has been proved times without number that the soundest policy is to progress by evolution. If 1921 fashions in ladies' attire had been introduced in 1896, the wearers in all probability would have been stoned; whereas, by a process of gradual evolution, what was impossible in 1896 becomes an accepted fact in 1921.

From the Buyer's Viewpoint.

The pressed steel Janoir, with 8 h.p. flat twin engine.

More on Janoir

Such designs as the Janoir and one or two others impress one in this light. They are opposed to accepted ideas of to-day, and on that account may be difficult to market commercially.

Thus the main tendency in one section of the French trade may be said to be revolutionary design based on a genuine belief that the public will appreciate the aims of the designers. But often the engineer's sense of proportion goes astray, and we should say that much of the ingenuity of such machines as the Janoir, Lutece, Louis Clement, Bleriot, and Peugeot front wheel drive will be lost on a public which is not composed of engineers. Excellent as are the pressed steel frames of the Louis Clement and Janoir, the buyer may be inclined to ask if they possess any great advantage over their contemporaries having tubular frames. To be justified, an innovation must have some great advantage, and, while the engineer may agree that certain machines are excellent specimens of engineering talent, the buying public may demand to know whether such construction signifies any advantage to them. Is it cheaper? Does it render a machine more accessible, or lighter, or easier to control? It is not sufficient to claim that pressed steel is better than tubes. Buyers require to know why, and answers based on theories carry little conviction nowadays.

Such is our view of unconventionality after contact with the motor cycle movement since its inception.

Motor Cycles at the Paris Salon

OCTOBER 13th, 1921. p445

The Conventional Designs.

Bleriot 500 c.c. side-by-side twin four-stroke, which embodies a concealed rear springing system. The disc wheels are built up from steel pressings.

More on Bleriot

The Gnome-Rhone, a machine which conforms to British ideas of clean design and finish

The engine has an outside flywheel and the gear fitted is a Sturmey-Archer three-speed.

More on Gnome-Rhone

In passing on to the next group of motor cycles "the conventional types" one can summarise them in a very few words. Mostly they are fairly good imitations of popular British makes, using in some cases well-known British components in the usual British way, but in doing so the makers have perpetrated some of the errors of British makers of a decade ago.

It is not with such makers, however, that the rise or fall of any industry is dependent, and their sphere in the world of wheels is to supply a known and existing demand, and not to seek to advance the motor cycle movement. They neither make nor unmake history : they merely assemble well-known units, and compete with their confreres using the same units only on matters of price, equipment, or finish. Engine and gear unit manufacturers make the entry of small motor cycle makers into the industry quite an easy matter, and it is therefore not surprising that several of these machines are fitted with English-made power units and gear boxes or the engines and gears of component manufacturers in France.

The apparent popularity of any particular type is not entirely genuine, if judged by assembled machines, as one maker producing, say, a really good two-stroke engine may induce many firms to fit that engine, but the chances are just as much in favour of another engine maker who markets a four-stroke. In England, the J. A. P. four-stroke and the Villiers two-stroke are fitted by the majority of "assemblers"; in France the Ballot two-stroke and the Zurcher four-stroke occupy similar positions.

As in Great Britain, this section of the industry prefers not to specialise on any particular model, but offers both four and two-strokes, with and without two-speed gears, and, in the former types, with the option of clutch and kick-starter.

Auxiliary Engines.

Any visitor to the Grand Palais must be impressed by the large number of small engines fitted as auxiliary power units to pedal cycles. In this category we have conditions entirely different from those prevailing in the first two groups already referred to. Undoubtedly the number of these small units reveals the real crux of the whole position of the French motor cycle movement. France is a great cycling country and always has been, and it is considered that the greatest demand for power-propelled machines will eventuate from ordinary every-day cyclists.

In England motor cyclists form the greatest fraternity of any section of road users. There is nothing to be compared to it; but in France only the nucleus of a similar fraternity exists, therefore the strictly utilitarian machine must be considered, and a low-priced motor-propelled pedal cycle is the result of that consideration.

In this group of machines we have conventionality and unconventionality, but at times the two are so cunningly blended that to the purchaser with, as yet, undeveloped ideas of what is, and what is not, approved engineering practice, all are equally attractive.

In this section the many makers appear to have deliberately set out to avoid perpetrating anything similar to their competitors, and it is impossible to say that there are any particular tendencies, for the reason that no maker has tackled the proposition in the same manner. It is astonishing the number of ways and means that can be adopted with a little ingenuity, and the French are nothing if not ingenious. Thus at the Paris Show there are tiny two-strokes and four- strokes utilising every form of mechanical transmission. Perhaps friction drive is a little more popular than any other, for one has a small pulley engaging with the front tyre, another a flat pulley in contact with a flat faced rim on the side of the rear wheel, and a third within the hub of the front wheel. Some have belt drive, others chain or gear transmission. Some are fitted in the frame, others on the carrier, or on the handlebar. The majority are two-strokes, and of the four-strokes some have automatic inlets and some are at the other extreme with mechanically operated overhead valves and detachable heads; and they are placed in all positions, vertical, inclined, horizontal, and even "upside down."

Motor Cycles at the Paris Salon

OCTOBER 13th, 1921. p446

General Impressions.

As is to be expected from a nation so long identified with the manufacture of pedal cycles, the cycle work of most of the French exhibits is exceptionally good, but with a few exceptions, the mudguarding is capable of great improvement. Tanks, too, are somewhat rough, but strike one as being constructed of much stouter material than those of British machines. Welded frames appear to be much favoured, and very excellent results, so far as appearance ~ is concerned, are obtained. The locking ring on the steering heads is usually knurled, while the detail work of forks is good.

Front Forks.

The kinds of front forks are many, and the majority are of the type which embodies blades hinged or pivoted directly below the steering column, and not a few utilise the principle of the well-known Triumph fork. Not a few have forks of the parallel link type on the lines of the Druid, while the well-known British fork units - Druid, Brampton, and Saxon - are included.

Tyres.

Taken on the whole, the size of tyres adopted is ample for the weight of the machine. In one case 710x90 mm. tyres are used, which, so far, appear to be the largest tyres yet used on a motor cycle.

Almost without exception, mudguards are insufficiently valanced, especially front guards, which generally have no valances at all forward of the forks. Silencing, too, has not received the attention due to it, and usually very small silencers are fitted, which are equipped with cut-outs.

In several designs means have been adopted to minimise faults where eradication should have been attempted. For example, the Peugeot Co. are responsible for a front fork, which requires a rubber buffer to prevent shock when the forks strike the head.

Name plates in lieu of transfers are fitted to many of the machines, and while these have a good appearance when new do not assist cleaning, as they present so many sharp projections to catch the cleaning rag.

Brakes.

French motor cycles are not well equipped with regard to brakes. On a large number of machines only one brake is fitted, and where the equipment includes two brakes they are usually fitted to operate on the same belt rim. In a few cases the brakes are side by side, one working in the V of the rim and the other on the flat extension between the V and the wheel spokes. Internal expanding and the external types are in evidence on the newer designs, but, taken generally, the brake work is not what one would expect from France. At least one solo machine has a hand brake similar to the clutch lever of an American machine.

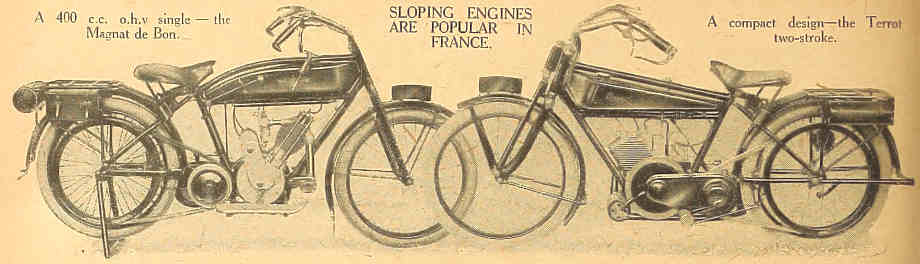

(L) The Magnat Debon, a 400 c.c. four-stroke with overhead valves. It has a two-speed gear, chain-cum-belt transmission, and a cone type clutch. The design appears to be somewhat spoiled by the single forks fitted. (R) The Terrot two-stroke, an exceptionally well finished machine, following more or less conventional lines. Observe the square fins, and the spare petrol tin and circular tool box on the carrier.

Motor Cycles at the Paris Salon.

OCTOBER 13th, 1921. p446

Another unconventional type - the Bleriot two-stroke side-by-side

twin. It has two crank chambers with a clutch disposed between

them, and drives through spur gears in a unit three-speed and

reverse gear box.

More on Bleriot

Bleriot sidecar suspension system. The

arrow indicates the position of the wheel

hub.

More on Bleriot

Now fitted with a two-stroke engine of 500 c.c, the Louis Clement appears in an improved form. It has pressed steel frame and forks.

More on Louis Clement

THE PARIS SALON AT A GLANCE.

Features of 1922 French Motor Cycles.

Pressed steel construction.

Welded tubular frames.

Side-by-side twin engines.

Superb sidecar bodywork.

Auxiliary engines numerous.

Nearly thirty British makes represented.

Single - cylinder Two-strokes are fitted to the following motor cycles; Terrot, Peugeot, Soyer, Motosolo, Plasson, Alcyon, Thomann, D.F.R., Yvels, Louis Clement, Supplexa, Blanche Hermine, Armour, and Labor. Single-cylinder Four-strokes to the under-mentioned : Griffon (two types). Ultima, Gnome-Rhone, Magnat, Labor, Otobiron, Alcyon, Thomann, Armour, Yvels, and Viratelle.

Side-by-side Twins. Four-strokes: Bleriot, Lutece, and Viratelle. Two-stroke : Bleriot.

V Twins : Rene Gillet, Griffon, Alcyon, and Oriol.

Flat Twins : A.B.C. and Janoir.

Water-cooling is favoured by the makers of the Motosolo and Viratelle (two types).

Overhead Valves : Griffon, Magnat, and Otobiron.

Considering that at least three large engine unit manufacturers - Anzani, Train, and Sicam - all have remarkably extensive ranges of engines, which would permit every assembler in France to have a distinctive type or size to himself, one cannot help but marvel how the temptation has "been resisted.

French engine design deserves every commendation, and many different two and four-stroke models are available. French motor cycle assemblers have the choice of several sizes in all types, including flat twin four-strokes from about 200 total c.c, several sizes of single-cylinders, and a variety of V twins from 750 to 1,100 c.c. - some with overhead valves, and both air and water-cooled. In two-strokes there are singles and side-by-side twins of several sizes, also obtainable either air or water-cooled.

The rear position for the magneto is favoured by most of the French manufacturers, while in the case of single-cylinder engines an inclined position appears to be preferred, but this apparent tendency is misleading on account of so many fitting a proprietary two-stroke engine, which is designed to be so located in the frame.

Seventy Different Makes Represented.

Excluding the dozen or so auxiliary motors, no fewer than thirty French makers of motor cycles are exhibiting at the Paris Salon, a really excellent entry for a young industry. In addition, there are examples of Belgian, American, and Italian productions, besides nearly thirty British makes of motor cycles and sidecars on view.

Spring Frames.

It is to be expected that as bad roads are rather more the rule than the exception in France, designers would give consideration to the question of spring frames. The A.B.C. and the three newer designs (Janoir, Lutece, and Bleriot) are so equipped; therefore one may conjecture that there is a tendency in this direction.

Engines.

The details given below will show the tendency in engine types, and will reveal the surprising fact that probably the most unsuitable type of engine for motor cycles, the side-by-side twin, is represented by four different machines, while the well-tried V twin so general in this country is used as the power plant for a like number.

Motor Cycles at the Paris Salon

OCTOBER 13th, 1921. P447.

THE EXHIBITS DESCRIBED THE UNCONVENTIONAL TYPES.

UNDER this heading reference has already been made to the Janoir motor cycle; and as an unconventional machine it certainly takes first place. As will be seen from the illustrations, it not only employs a pressed steel frame, but its general outlines are quite the reverse of the accepted idea of what a motor bicycle should look like. It is sprung fore and aft on leaf springs, and a spring saddle is not considered necessary. We described an earlier model of this ingenious design at the time it was exhibited at the last Paris Salon, and our illustrations suffice to show its main points of interest. The sidecar, which is marketed with it, also has a sprung axle.

Car Practice.

The Lutece is unconventional in another direction, and conforms more to accepted motor cycle practice plus certain features borrowed from the car. It has a vertical twin engine with gear box integral with the crank case, and the final drive is by shaft. Like the Janoir, it is sprung at the rear on leaf springs, but no torque rods are fitted, and stays, pivoted at the rear of the saddle, are intended to ensure lateral rigidity.

The Louis Clement is another pressed steel machine which made its debut at the last Paris Show, and which now appears in an improved form. In 1919, however (there was not a show in 1920), a twin-cylinder model was exhibited, and this has been abandoned in favour of a Train single-cylinder two-stroke of 500 c.c. capacity.

Side-by-side twin engines are favoured by the Bleriot Company, for, in addition to the four-stroke two-cylinder model now established on the French market, a twin two-stroke of 750 c.c. capacity is introduced this year finished, in fact, a few days before the Salon opened. Like the four-stroke model, the gear box forms part of the crank case, the clutch is located between the two crank chambers, and there are three speeds and reverse, the latter, perhaps, more by accident than intention, since the power unit was designed for and is fitted in the new French Bleriot cycle car. The machine presents quite a good appearance, but there is still a certain amount of experimenting to be done before the model will be offered to the public, such points as economy and silence not yet having had very close attention.

EXAMPLES AND DETAILS OF SOME OF THE UNCONVENTIONAL DESIGNS AT THE SALON.

Side-by-side twin water-cooled Viratelle, with radiators on the side of the tank.

More on Viratelle

One of the several miniature motor cycles, the Monet-Goyon. Machines bearing this name, and engined with small four-stroke power units, are offered to the public in many forms. Monet & Goyon

The only full-powered lady's motor cycle in the exhibition, the Soyer. It is of very pleasing design, exceptionally well made, and the tank forms part of the frame. The engine fitted is a two-stroke having a detachable head.

More on Soyer

Details of the Bleriot two-cylinder two-stroke power and gear unit, showing the lower half of the crank case, the gears, and pistons.

The last machine in this group is the Viratelle, which was seen outside Olympia last November. It has a water-cooled side-by-side four-stroke twin engine, placed across the frame, with integral gear box, the final drive being by chain. Two circular radiators are located at the fore end of the tank. A single-cylinder model on similar lines is also exhibited.

Motor Cycles at the Paris Salon

October 13th, 1921. p448

THE CONVENTIONAL TYPES.

PROBABLY the nicest motor cycle in the Show from the English point of view is the French-built A.B.C. Although unconventional two years ago the design is now so well known that we place it in the category of the conventional. Several minor amendments have been made to the original Bradshaw design. The internal expanding brakes on both wheels are larger, the hot air muff on the induction pipe has been increased in area, and the overhead valve rockers are fitted with extra Avire springs. Another addition is an oil circulation indicator fitted on the top tube, and forms the centre of three dials, the speedometer and clock being the other two, neatly disposed at the front end of the tank and protected by in-turned extensions of the leg guards.

A Franco-British Machine.

Exhibited alongside the A.B.C. is a new production, the Gnome-Rhone, a taking looking machine quite on English lines. The engine is a four-stroke single of 500 c.c, having an outside flywheel and a cylinder reminiscent of the Triumph. Chain-cum-belt transmission is adopted, with a W.D. type Sturmey-Archer gear. The mudguarding is exceptionally well done, the side extensions being part and parcel of the main guards and of stouter metal than is usually adopted by British manufacturers.

Taken generally, the French makes, with old-established reputations in this country, are somewhat disappointing. One would expect something distinctive from the Peugeot concern, but apart from a novel front wheel-driven motorised bicycle, the Peugeot models are no different from their many contemporaries fitted with proprietary units. Other mediocre machines with old names are the Terrot, Labor, Alcyon, and Rene Gillet, all of which fit proprietary units. Taken on the whole, they are quite good for the market they are intended to supply, but it seems sad that in, an industry that once led the way the pioneers should display so little enterprise.

The Griffon, another well-known French motor cycle, is an exception, and three distinct types are exhibited. The first is little more than a motorised bicycle, but has a tiny and beautifully made four-stroke engine with overhead valves; the second type is a four-stroke lightweight approximating to the popular J.A.P.-engined lightweight in Great Britain; and the third a V twin of 6 h.p. Both the two last-mentioned models are fitted with Burman gears.

On English Lines.

Previously known as the G.L. - a machine which competed in the 1919 Six Days Trial - the M.A.G.-engined Oriol follows accepted British practice, and some minor details, such as the foot plates and silencer, are carried out in a very neat manner. On the other hand, the finish of the mudguards is poor.

Such names as Ultima, Thomann, Armour, D.F.R., Supplexa, and Blanche Hermine grace the tanks of quite conventional types of motor cycles, while the Yvels - the winner of the 250 c.c. class in the Grand Prix - is also on view. A machine known as the Motosolo has a two-stroke engine - one water-cooled, with the radiator neatly arranged in the fore end of the tank. The Magnat is a 3 1/2 h.p. four-stroke with overhead valves, and the Soyer a neat two-stroke with detachable cylinder head. The only full-powered lady's model in the show is exhibited by this firm. It is a well-designed machine with an open frame, and a tank which forms a part of the frame. We were informed that there are, however, very few lady motor cyclists in France, which is somewhat surprising considering the activity of French ladies in other outdoor pastimes

SUPER SIDECARS.

WHEN we say the French motor cycles do not come up to the English as regards design or finish, we may be forgiven, but as regards sidecar bodywork, upholstery, and finish the French have us badly beaten. There is no doubt that quite the finest sidecar carrosserie yet attached to motor cycles is now on view at the Paris Salon.

There is a distinct tendency to follow boat design, and one attractive feature is the varnished light wood deck which contrasts pleasantly with the painted or varnished natural dark wood of which the rest of the body is usually built. There is an excellent example of this on the D.F.R. stand, where the coachwork referred to is by G. Gille, of Puteaux. Perhaps the highest class example of French sidecar coachwork is to be seen on the A.G. stand, where two bodies at once strike the eye. Of these, one is practical and the other highly and exquisitely ornamental. The practical body is an attractive looking and thoroughly sound piece of work. The chassis is mounted on semi-elliptic springs, while C springs support the body, which is not only comfortable but of pleasing design.

A special trunk is supplied, which fits behind the body. The hood is quickly detachable and easily folded so that it can be stowed away in a box made for the purpose and fixed near the step. The finish is excellent and far superior to that found in similar examples of this type of work in England. The other body is obviously specially got up for the Show, but is nevertheless interesting, as it demonstrates the length to which luxury sidecar bodybuilding can go. The style is Louis XV., and the body follows closely the design of a luxurious sedan chair. There are the four-pane plate glass windows, the graceful curves and lamps of the same period, while suitable carving (really moulding) and upholstery complete this unique body. The appearance of such a turnout on the Portsmouth Road would lead to such a scene as might be better imagined than described.

Motor Cycles at the Paris Salon

OCTOBER 13th, 1921. P449

The height of the Bleriot sidecar appears to be absurd, but French passengers desire to be on a level with their drivers in order to be sociable. Bleriot

A real dinghy sidecar on the Lutece. It is superbly finished in the natural colours of the wood - teak for the hull and bird's-eye maple for the deck.

More on Lutece

On the Indian stand, the Ceel sidecar is well worthy of mention. It is of the two-seated variety, and it must be stated here that until this year double-seated or multi-seated sidecars were unknown in France. Built of steel, there is no doubt that the Ceel is not only smart, but quite practical. The front passenger has ample leg room, and the rear passenger enough. Each has his own windscreen, and the hood protects both. It is interesting to note that the front passenger occupies the centre of the body, so that if only one seat is filled the balance is correct. The spare wheel, carried at the rear, is slipped over the tail and carried in a suitable bracket.

Boat Body Building.

A side car on the Lutece stand is so like a boat, having a correct bow and a yacht pattern stern, that it looks as if one could rig a small mast and sail, put it in the water, and sail away. The deck is of varnished bird's-eye maple and the hull of mahogany, copper fastened - a very pleasing contrast - and, curiously enough, these boat pattern bodies do not look too uncomfortable. Tony-Bouley show a wide family sidecar with staggered rear seats and a seat in front for the child. The same firm also show a handsome two-seated body, with doors giving access to each seat.

THREE-WHEELERS.

So far as three-wheeled cycle cars are concerned, the French-built Morgan is the sole genuine example. Four models of this make are shown - two water and two air-cooled. Of the former one is a sports type with a rather deep back to the body, and what seem to be slightly wider seats. The single screen is of rather unconventional pattern, as it is hinged near the top, while no hood is supplied. The other water-cooled model is the touring pattern. The air-cooled Morgan is provided with upright backs to the seats, which do not look too comfortable, and there seems little protection in the low-sided body. A well-finished polished chassis is also shown on the stand, while it is interesting to note that M.A.G. engines are fitted in all cases.

We have thought for a long time that the old forecarriage was dead, buried, and well-nigh forgotten; but Ajasson de Grandsagne has attempted its revival. He argues that the forecar is more safe and more rigid than the sidecar, it only pays the motor cycle tax in France, and has never been tried on a three-speed- cum-clutch motor cycle of modern construction. He does not seriously intend it for passenger-carrying, but rather for transforming a motor bicycle into a tricycle for winter use and for the transport of light goods in a suitable box carrier.

Two examples are shown - one fitted to a Powerplus Indian, in which case the longitudinal members terminate at point below the saddle, thus avoiding interference with the rear springing; while the other is fitted to a 4 1/4 h.p. B.S.A. The design has been modernised, in so far as the fitting of sprung front axles, coil springs being used.

Source: The Motor Cycle, Oct 13th 1921

If you have a query or information about this event please contact us