SHE cost me thirty shillings, did my 1½ h.p. front-drive Werner, back in 1903, and I shall never be able to buy so much fun for the money again. A schoolboy is not over plentifully supplied with cash (or should not be), and the indulgent cycle-maker who let me have her accepted half-crown installments, at irregular intervals. Even then she was a wondrous antique, but her tyres (French racing Dunlops) were thoroughly good, her frame strong enough for a modern twin, and her engine was a splendid job.

That was a proud moment when, after an overhaul lasting weeks (needless to say the price included the right to do all the necessary tinkering in the seller's workshop), we bore her down the steps. I had done my best to transform her into the outward semblance of a speed monster: the saddle had been removed, and a rickety luggage-carrier intended for a cycle substituted, liberally padded on top, the exhaust arrangements and pedalling gear scrapped, and in the place of the latter a piece of broomstick (wrapped with inner tube to conceal its domestic origin) did duty for footrests. (One had to mount gingerly.)

My Very Own!

I sat astride her in the road, regarding the engine with affection and pride. Please remember that I was sixteen, she was my very own (for had not the first half-crown been paid?), and I had never been on a power-driven machine before. The kindly cycle-maker and his apprentices pushed lustily. We swayed down the road in wide arcs. She fired. Oh, irrecoverable moment I Never was such a bark as that baby engine possessed. They lodged complaints in the Maida Vale flats about me, because I would run up and down half the day wondering if it wasn't really possible to do something in the way of tuning on a surface carburetter.

Little Werner and I careered down the road, keeping an eye out for people who might know us, and be impressed. We rounded the first comer successfully, but on straightening up side-slipped on a tramline, and went down with a slam. (That was her first naughty trick, and her last: with the engine over the front wheel the little machine steered perfectly, and could be ridden "hands off.") I recovered my steed; a little acid spilt from the accumulator and some petrol (tenpence a gallon, so it didn't matter) was all that was lost, and we ran soberly round the houses back to where the expectant staff awaited us. That was the beginning of a jolly time. A man named Arthur Cummings, who was very prominent as a speed exponent on the 70 x 70 class, used to haunt Paddington track near by. I showed him Werner. He was too well-mannered to laugh, and took her and my efforts to make her do thirty miles an hour seriously. We bought a drill, and started to tune her.

Tuning for Power.

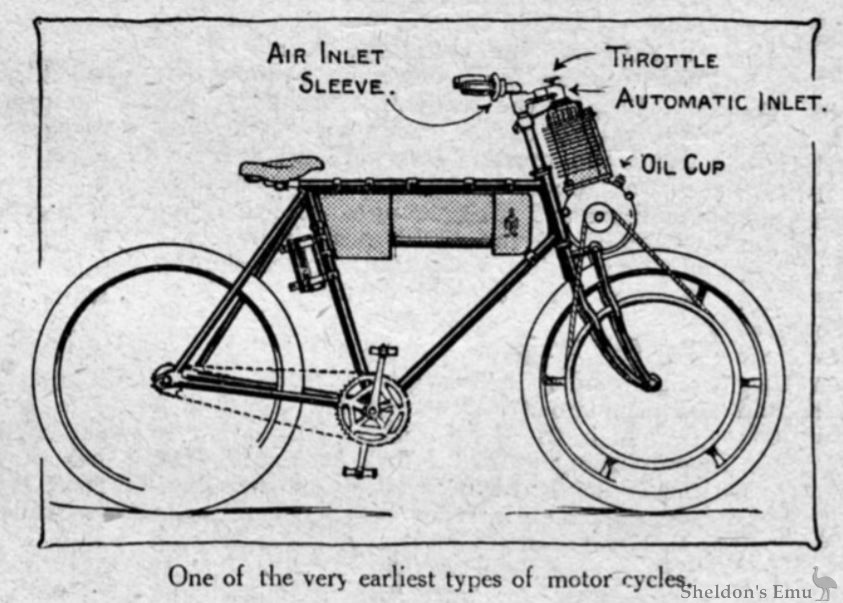

The air intake to the engine was governed by a revolving sleeve on the handle-bar, and the neat mixture was led from a surface carburetter forward of the tank up the head column to the handle-bar lug, where the engine was bolted on. Drive was by twisted round belt (and some of you think a V belt is troublesome!) to a pulley on the front wheel, and you carried your oil in a little glass cup on the crank case. Coil and accumulator conspired together to defeat dull care: one or the other or both always needed attention. The band brake on the back wheel was splendidly efficient — until one day it broke; after that I remember I used to stop by dragging my feet on the ground and using the compression. (There is undeniably a special providence for mechanically-minded schoolboys).

We removed the gauze from the induction pipe, and while this ran her consumption up terribly, it was worth it. I ran her to Brighton and back in days when none ventured on pedalless machines, and she took everything except the last stretch of Handcross. There her proud owner had to slip off and run ; but she was forgiven, for it was a plucky climb for an engine aged and so small.

By this time we were regular habitués (sixpence admission) at Paddington track. One day we borrowed a back wheel from a racing push-cycle, with a fabric-sided tyre about the diameter of a lead pencil, and a slender wood rim and cobweb spokes. We inserted this in the back forks, gave Werner an extra swig of oil, and issued a formal challenge to a neighbouring youth who owned a wheezy 3 h.p. Kelecom. It was a Homeric struggle. I flattened myself along the top bar until I could flatten no more, sprayed with hot oil, and unutterably happy because the dreaded Kelecom was well behind. It was a famous victory, but as she crossed the line poor Werner seized.

Her piston had gone. We disembowelled a worn-out Yankee "Thomas" that we had access to. Some brisk work with a file, and the old rings, and the little engine was got going again — a thought metallic in the exhaust at speed, but serviceable. I always feared it was the drilling we did on that piston; we used much enthusiasm on the job, but little discretion.

Poor little 'bus. I suppose her rusty bones are lying in some forgotten corner. Still, I think in her time she gave a keener pleasure than my little opposed twin, now waiting in the shed, eager and twice as speedy, can ever give.

R.H.B.

The Motor Cycle, November 22nd, 1917. Page 495

Martin Shelley writes:

"Some years ago, a mystery engine was brought to one of our group lunches in Stirling, and after much deliberation, it was thought to be from a Werner although it bore no markings to help confirm its identity. I left the meeting determined to try and shed more light on the mystery engine and was amazed to discover it bore the consecutive number to the Science Museum’s Werner which had been owned and ridden by Cecil Burney, cofounder of Burney & Blackburne and first secretary of the flegling VMCC in 1946; Cecil was one of the characters who appeared in Captain WHL Watson’s classic book, Adventures of a Despatch Rider which we had republished as Two Wheels To War a few months before. I am now attempting to put together a running example so I can test the theories about how stable (or otherwise!) these primitive machines are in reality.

In 1917, a schoolboy wrote a piece about his encounter with just such a machine which I reproduce here as printed, and you get an idea that it was actually rather better than its reputation would have you believe. I have suspended my disbelief for the moment until I can test it for myself, following in Tony’s bold footsteps."

The Early Motor Bicycle, October 2020.

If you have a query or information about about the Werner brothers please contact us