CHAPTER V

HOW THE ENGINE WORKS

IN these days, when the internal combustion engine is of such vast service in so many spheres of locomotion when it provides the motive power for airways that are rapidly spreading throughout the world, when it is mechanicalizing great armies, and when it is giving millions of people the facilities for enjoying healthy recreation in the way of motoring, yachting, and other sports' there are, perhaps, few people who have no glimmering as to how the four-stroke internal combustion engine works. Nevertheless, in a book primarily designed to meet the needs of the novice, a brief explanation of the behavior of the four-stroke cycle engine can scarcely be omitted.

During the titanic struggle in Europe, which waged incessantly from 1914 to 1918, the petrol engine progressed by leaps and bounds. This was brought about through dire necessity. The belligerent which had the mastery of the air was at liberty to bomb and photograph every part of the enemy's lines, and to wreak havoc and destruction miles in their rear. Thus the frantic race for supremacy in engine design went on year after year, for the performance of aeroplanes depends largely upon the weight/horse-power ratios of the engines installed. But the fundamental principle upon which the four-stroke engine works has not altered one iota, and probably never will. True it is that wonderful inventions are made from time to time take, for example, the Constantinesco Torque Convertor but basic principles remain unaltered. Those who have some knowledge of the 'Otto,' or 'four-cycle' stationary gas or oil engine, start with a considerable advantage in the study of the petrol motor, because the principles involved are identical in each case, although the mechanical differences are very great.

THE FOUR-STROKE ENGINE

Coal gas and several other gases become explosive when mixed with certain percentages of air (or oxygen), the percentage varying with the particular gas used, and, to a lesser extent, with the character and temperature of the atmosphere, so that a certain gaseous mixture imprisoned in a space (called the combustion chamber) will, if ignited, exert a pressure in all directions due to the rapid rise of temperature on combustion ; and here it is well to impress upon the reader the fact that all internal combustion motors are heat engines, i.e. they derive their power from the intensely rapid production of heat at the moment of explosion ; and it should further be noted that the more rapid the ignition, and the more complete the combustion, the greater will be the power of explosion- Strictly speaking (turning to the ridiculous), an H.E. bomb is a heat engine - an engine capable of vast destruction, including itself! To effect complete combustion it is essential that the mixture is correct. In the case of the petrol engine, a good explosive mixture contains by weight about 93 per cent of air and 7 per cent of petrol. Any variations from this proportion will result in the combustion being incomplete, or slow. In the latter case the mixture will burn rather than explode - after all, the only difference between burning and exploding is that intensely rapid burning generates great heat in an infinitesimally small period, with the result that a loud bang (called an explosion) occurs when the hot exhaust gases come up against the atmosphere. The importance of having complete combustion will be seen later. Incomplete combustion necessarily entails a considerable loss of power.

A crude illustration of the basis of gas engine or petrol motor construction may be given if a coffee canister with tight-fitting lid be imagined to be filled with the explosive mixture, and by some means the contents ignited ; the result would be that, the pressure in all directions being equal, a violent explosion would hurl the lid far away; but if for that loose lid we substitute the piston A, Fig. 28, a close sliding fit in a fixed cylinder B, the piston being directly coupled to a crank C, by a connecting rod D, the shaft E, on which the crank is fitted, will now have reciprocatory movement of the piston transformed into rotary movement of the shaft, and, at the moment of explosion, the shaft will begin to rotate. Suppose the shaft E is attached to a wheel F called the flywheel; then this wheel will be set in rotation also. Being purposely made heavy, it will go on spinning for some time - in fact, if there were no friction it would go on for ever owing to the kinetic energy it derives from the initial explosion by virtue of its inertia, and will cause the piston to reciprocate in the cylinder. It can clearly be seen that the piston makes two strokes for every revolution of the flywheel. Let us assume that the explosion has just occurred, and that the piston after reaching the bottom of its stroke, is ascending again. Imagine a valve at the top of the cylinder to be open during this stroke. Then the products of combustion will be swept out of the cylinder Similarly it is easy to see that, if on the commencement of another down stroke, a second valve opens admitting an explosive mixture, while the first valve closes, the cylinder can be recharged with gas during this down stroke. If, on again reaching the bottom of its stroke, both valves close, the charge of gas will be trapped and compressed during the ensuing upward stroke ready for the next explosion. Thus, clearly, the flywheel can be made to rotate continuously, so long as provision is made for supplying the explosive mixture and causing a spark to take place at the right time. The explosive mixture is supplied by what we call a carburettor, and the spark by a magneto. We will for the present confine ourselves to a more detailed description of the four-stroke cycle. Let us refer to Fig. 29, which illustrates the cycle of operations very clearly.

Two valves are fitted in the cylinder head, namely, the inlet valve and the exhaust valve. When both these valves are closed upon their seatings, the space above the piston is a sealed chamber.

If the inlet valve is open, the cylinder is in communication through the induction pipe with the carburettor. If the exhaust valve is open, the cylinder is in communication through the exhaust pipe with the silencer.

We will now suppose that the piston has just reached the top of its stroke after sweeping out through the open exhaust valve

the hot gases left in the cylinder after a, firing stroke. During this upward stroke the inlet valve has, of course, remained closed, for otherwise the hot gases would have had access to the carburettor via the inlet valve, with dire consequences that may be left to the imagination. The two valves are open and closed at the correct moments by cams upon the half-time shafts driven by gearing off the engine shaft at half engine speed. Fig. 30 illustrates how a valve tappet A is operated by a cam B, with rocker C, on a half-time shaft D, driven by a gear wheel E, off the engine pinion F. See also Fig. 54.

As the piston reaches the top of its 'sweeping-out,' or exhaust stroke, the exhaust valve closes, and a moment afterwards the inlet valve opens. This is the point from which we shall assume our four-stroke cycle to begin, and we 4 shall consider exactly what happens during the four strokes which take place before we arrive back to the starting point and begin a fresh cycle. The four strokes are called the induction stroke, the compression stroke, the firing stroke, and the exhaust stroke.

1. Induction Stroke. The exhaust valve has now closed, and the inlet valve has opened. The downwardly moving piston has to fill the space behind it with air.

This produces an intense draught or suction through the induction pipe and carburettor. The blast of air sweeping over the small aperture, or 'jet,' to fig. 30. valve cam which a supply of petrol is constantly action fed, causes a fine jet of petrol to rise like a fountain in the carburettor. The fountain resolves itself into spray, or is 'atomized,' and the 'mixture,' consisting as it were of air converted into a fog by the tiny petrol particles, passes along the induction pipe into the cylinder. If the induction pipe is warm the fog may, of course, evaporate before it reaches the cylinder, a true mixture of air with the petrol vapour being then supplied. In any case the fog will be evaporated by the warmth within the cylinder itself. At the end of the downward stroke of the piston the inlet valve closes, and the cylinder becomes a sealed chamber containing the explosive mixture.

Page 72

2. Compression Stroke. The crank on the engine shaft, assisted by the flywheels, passes over its dead point, and the piston commences its upward stroke. The well-fitting piston rings prevent the escape of the mixture on charge into the crankcase chambers, and the charge undergoes compression. The amount of compression effected during the stroke depends, of course, upon the design of the engine, that is to say, upon the relative volume of the whole cylinder when the piston is at the bottom of its stroke to the space left above the piston when it has reached the top of its stroke. This is called the compression ratio. Gases, as we all know, are heated by compression, and consequently, if a gas is quickly compressed to, say, one-fifth of its original volume, its pressure is increased considerably more than five times. As a result, the pressure at the end of the compression stroke in an engine having a 5 : 1 compression ratio is well over one hundred pounds to the square inch.

3. Firing Stroke. We have now reached the moment at which the charge is to be fired. The inlet and exhaust valves are closed, the charge is fully compressed, and all is ready for the explosion. This, of course, is brought about by the properly timed passage of an electric spark between the electrodes, or points, of the sparking plug. It might be supposed that this spark should occur just as the piston reaches the top of its compression stroke. This, however, is not the case. The correct time for the spark depends upon the speed at which the engine is running. The reason for this is clear when we consider that no explosion - not even the explosion of cordite in the breech of a howitzer - is absolutely instantaneous. In the case of an explosive mixture of air and petrol vapour, the explosion takes quite an appreciable time, and there is a lag, so to speak, between the passage of the spark and the moment when the exploded charge reaches its maximum temperature and pressure. If, therefore, the engine is running fast, the ignition must be so far advanced (i.e. timed to take place early) as to allow the maximum pressure to occur when the piston has only just passed over its dead point. When ignition timing is correct, the maximum pressure may be taken as about 450 lb., and the average pressure during the working stroke as about 100 lb. per square inch. Of course, if the ignition is too far advanced, the exploding gases may administer a blow on the head of the rising piston, and produce a knock. The phenomenon of knocking is very curious, and is often the subject of heated argument. If, on the other hand, the ignition is not advanced proportionally to the engine speed, the full pressure will not be reached until the piston has moved an appreciable distance on its downward stroke, and some of the energy of the explosion will be lost.

Page 73

If by some mischance a gross error of timing were made in the direction of retardation, or lateness, so that the piston had moved far down the cylinder before the explosion occurred, the mixture would burn slowly instead of exploding, there would be little power, and the exhaust gases would be still flaming when they were finally allowed to escape, so the exhaust valve would be liable to be badly burnt. It is for a similar reason, namely, slow and imperfect combustion, that a weak mixture, containing an excess of air compared with the amount of petrol present, may cause burning of the exhaust valve. This effect of a weak mixture sometimes appears to the novice rather paradoxical. In point of fact, of course, the whole object of the internal combustion engine is firstly to develop heat, and then to convert it into work. If through the use of an unsuitable mixture, or by faulty timing of the ignition, the working conditions of the engine are such that the heat cannot entirely be transformed into work, we get the dual conditions of (1) loss of power, and (2) an excess of heat in the exhaust gases with consequent damage to the exhaust valve during the exhaust stroke.

4. Exhaust Stroke. The exhaust valve now opens, and the products of combustion are ejected from the cylinder into the exhaust pipe and silencer by the ascending piston. After undergoing cooling the burnt gases are now finally allowed to escape into the atmosphere.

THE PRINCIPLE OF THE CARBURETTOR

The problem of perfect Carburation is a very complex one, and as yet unsolved, for it is dependent on many factors. The chief difficulty which presents itself is the constantly varying engine speed and load. A certain mixture of petrol vapour and air is only suitable for an engine running at a certain speed and with a certain load, and should the speed or the load vary, the mixture should also be varied to meet the new conditions. Up to now it has not been possible to construct an instrument which will produce the necessary alterations exactly, and the best carbureting system is, therefore, a compromise. Other complications introduced are: the temperature of the engine and of the air, density of the atmosphere, and quality of the fuel. Petrol spirit used for ordinary motor work is a doubly distilled, deodorized spirit, of about -700 specific gravity, derived from crude petroleum. Other fuels, however, including benzol and paraffin, may also be used, but are not satisfactory except in the case of benzol, which is commonly used. Discol is frequently used for racing purposes. It is essential that a high-speed engine should run on a fuel having a high degree of volatility.

The carburettor is an atomizer, and its duty is to convert liquid petrol into a mixture of air saturated with the finest particles of are designed to (1) make the mixture as homogeneous as possible, (2) simplify the control, (3) enable automatic slow running to be obtained, (4) enable settings for special purposes to be made.

Measured in degrees of crankshaft rotation with a valve clearance of .006 in giving a valve lift of .3125 in. This diagram is interesting from a theoretical aspect only, for in practice the motor-cyclist never has occasion to retime his valves since the timing pinions are carefully marked (see page 128)

* The correct ignition advance in the case of all A.J.S. engines will be found in the specifications in Chapter 1.

xxx

fuel in the right proportions under all conditions; the correctness (approximate) is attained by either automatic, semi-automatic, or controlled means. In the case of the Amal carburettor (see page 79), used on all A.J.S. machines, the action is semi-automatic. The general principle on which all carburettors work will now be reviewed.

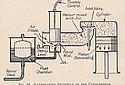

It has been found by experiment that the most satisfactory way of encouraging petrol to evaporate is to drive it under pressure through a very tiny hole, called a jet, and the process is assisted by heating the spraying device. Owing to the proximity of the carburettor to the combustion chamber, ample heat is, of course, conducted to it via the induction pipe, once the engine has warmed up. In practice it is not common to employ forced induction, or supercharging (i.e. to blow the mixture into the cylinder). Moreover, it is entirely unnecessary for normal requirements in the case of motor-cycle engines. The powerful suction through the inlet pipe on the inlet stroke can be relied upon to atomize the fuel completely. Let us refer to Fig. 32, which shows the salient features of a carburettor in action. It will be observed that the petrol level in the jet must be below the orifice at the top ; otherwise the petrol will overflow and cause flooding of the carburettor. The level is automatically regulated by the action of a float attached to a spindle, which operates a needle valve, thereby cutting off the petrol supply immediately the level in the chamber reaches the height of the jet orifice. On the downward stroke of the piston, air is sucked in through the air intake, past the partially open throttle, which is a closely fitting hand controlled slide, operating up and down in a barrel, past the jet, past the inlet valve, and thence into the cylinder. The extremely high velocity air current that must obviously sweep over the jet causes the fuel to issue in a small fountain, and simultaneously causes the spirit to be atomized and diffused with the air rushing in towards the combustion chamber. This, briefly, is the principle of the carburettor.

Actually, no carburettor is by any means as simple as that shown in the diagram, for consider the failings of such a carburettor. The rider will wish to vary the speed of his engine to meet various conditions ; he could do so by opening or closing the butterfly throttle valve or gas tap shown in the diagram. But, unfortunately, petrol and air are dissimilar vapours, and do not respond evenly to varying suctions; so the carburettor illustrated will give a mixture of different proportions for every throttle setting, and since petrol and air are only highly explosive when mixed roughly in the proportions of 13 : 1, only one of these settings will be correct. This might work tolerably well in the case of a stationary gas engine with a governor, but would be quite hopeless for all locomotion purposes.

The various refinements and complications that are incorporated in all modern proprietary carburettors (including the Amal)

Thus it is essential to be able to control the gas and air independently. This can be done by having two slides working independently, one for throttling the air intake and one for throttling the entry to the induction pipe (see Fig. 30). Hence, although the air intake may be fully open, a high velocity air current over the jet can still be obtained with the gas throttle only slightly open. And so the amounts of gas and air can be varied at will to suit the conditions.

THE IGNITION SYSTEM

The High Tension Magneto. This (a Lucas on all A.J.S. machines) is so called because, unlike an ordinary dynamo, it generates a small current at a very high voltage. An experiment that demonstrates this very convincingly(?) is to place a finger on the plug terminal while the engine is 'ticking-over.' The instrument is very complicated, and requires very delicate handling when being taken to pieces; no amateur ever dreams of dissecting a magneto. Magnetos of to-day are extraordinarily reliable instruments, and seldom give trouble. When trouble does arise, it can usually be located in the contact breaker (see page 121), and can be remedied easily by almost anyone. Therefore, we will conclude this chapter with the briefest description of the magneto, and how it works.

The magneto primarily consists of three parts (1) the armature, (2) a 'U' shaped magnet, (3) the contact breaker.

The armature comprises an iron core or bobbin of 'H' section, on which are two windings : firstly, a short- winding of fairly heavy gauge wire, and secondly, on top of the former, a very big winding of fine wire. The first winding is known as the primary and the second as the secondary should open the armature, which can rotate on ball bearings, is placed so that on rotation it periodically cuts across the magnetic field of the magnet, and creates a current in the primary winding. Incidentally, the contact breaker forms part of the primary circuit. This current, however, is at a very low voltage, far and away too small to produce anything in the nature of a spark. But if a break is suddenly caused in the primary by separating the platinum contacts when the current is at its maximum flow, a high voltage or tension current will be instantly induced in the secondary winding sufficient to jump a small space, if the circuit be incomplete. In this circuit the sparking plug is included, and things are so arranged that, in order for the secondary circuit to be complete, the current must jump across the electrodes of the plug, or, in other words, a spark must occur. Now in the case of a single cylinder engine, the points in the rotating contact breaker separate once in every armature revolution (there being one cam only), and the armature to which the contact breaker is fitted being driven off the inlet camshaft by sprockets and chain consequently runs at half engine speed; that is to say, a 'break' takes place once every two engine revolutions, i.e. four strokes of the piston. Hence if the initial 'break' be timed to occur when the piston is at the top of the compression stroke, all the other 'breaks' (and therefore sparks) will occur at this point also, and thus the engine will go on firing correctly. Besides the

'break' being timed to take place when the piston is in a certain position (which we call 'timing the magneto,' see page 124), it must also be timed to occur at the moment when the bobbin is having the greatest effect on the magnetic field (see Fig. 33).

This, of course, is allowed for in the design of the magneto, and does not really concern the reader. Also, it is essential that the primary circuit should be complete (i.e. the contacts must be properly closed) both before and after the 'break,' which should be of very short duration.

The cam ring, against which the cam of the contact breaker works, can be rotated by handlebar control through about 30', thereby giving means of advancing and retarding the spark.

The condenser is a device for the purpose of eliminating 'arcing, ' and the distributor, a 'brush' mechanism for distributing the H.T. current collected off the slip-ring (which is connected to the secondary) to the H.T. plug leads. A distributor is, of course, fitted only in the case of the Big Twins, and rotates at half engine speed.

For convenience in enabling the reader to obtain a better idea of the relation between the various parts and how they function as a whole, a wiring diagram of a simple magneto ignition system is given on this page. This diagram, if studied carefully in conjunction with the above general description of the H.T. magneto, should give an excellent idea of how that instrument, so often regarded as a complete mystery, operates. We will not enter into details of the method of construction since, as previously pointed out, beyond attention to the contact breaker (see page 124) the motor-cyclist is never likely to have cause to tamper with the magneto and is certainly ill-advised to do so. So much, then, with regard to the generating portion of the ignition system.

The Sparking Plug. Passing reference has been made in respect of the 'results' end of the system, i.e. the sparking plug. This small member requires and deserves some further consideration. It is astonishing how efficient modern sparking plugs are, considering the enormous heat they are subjected to, and the millions of hot sparks they are called upon to deliver during their working lives. The 'expectation of life' of the present plug is nearly double that of plugs made a few years back.

The purpose of the sparking plug is to provide at regular intervals a spark in. the combustion chamber.

The electric current for this job is generated, as we have seen, by the magneto. Fig. 35 shows the construction of a Lodge plug.

That shown is partly sectioned.

It comprises a piece of insulating material E held in a metal support consisting of the plug A and the gland nut B which are locked together firmly and screw into the cylinder head. Down through the centre of this insulator (usually mica, porcelain, or steatite) passes a thin metal rod D which is known as the centre electrode. To its upper end is attached a terminal F which holds fast the H.T. 'juice' wire from the 'mag.' At its bottom end are placed either one or two earthed electrodes (the plug shown has two) in close contact with, but not touching, the central electrode. Sparks jump from the centre to the earthed electrodes as soon as a current of sufficient voltage to jump the gap at the electrodes is generated by the magneto. Clearly the gap at the electrodes is of great importance (see page 122).

According to whether there are one or two earthed electrodes so is the sparking plug known as a 'single point' or a 'two point.'

SOME A.J.S. MECHANICAL DETAILS

The Amal Carburettor (fitted to all present models). This instrument combines the best and most useful characteristics of both Amac and Brown and Barlow instruments. It is thus a thoroughly 'brainy' job, and gives remarkable results. On the opposite page is shown a sectional view of the Amal two-lever carburettor, and its working will now be described. It is presumed that the reader is cognizant of the principle of the carburettor already clearly set forth. Space and time will therefore not be wasted in proffering redundant information on the action of the float, etc.

In connection with the float chamber of the Amal it should be pointed out that alteration in the float position can only have detrimental results.

Referring to the sectional diagram which illustrates the construction, A is the carburettor body or mixing chamber, the upper part of which has a throttle valve B, with taper needle C attached by the needle clip. The throttle valve regulates the quantity of mixture supplied to the engine. Passing through the throttle valve is the air valve D, independently operated and serving the purpose of obstructing the main air passage for starting and mixture regulation. Fixed to the underside of the mixing chamber by the union nut E is the jet block F, and interposed between them is a fibre washer to ensure a petrol-tight joint. On the upper part of the jet block is the adaptor body H, forming a clean through-way. Integral with the jet block is the pilot jet J, supplied through the passage K. The adjustable pilot air intake L communicates with a chamber, from which issues the pilot outlet M and the by-pass N. The needle jet O is screwed in the underside of the jet block, and carries at its bottom end the main jet P. Both these jets are removable when the jet plug Q,, which bolts the mixing chamber and the float chamber together, is removed. The float chamber, which has bottom feed, consists of a cup R suitably mounted on a platform S containing the float T and the needle valve U attached by the clip V. The float chamber cover W has a lock screw X for security.

The petrol tap having been turned on, petrol will flow past the needle valve U until the quantity of petrol in the chamber R is sufficient to raise the float T, when the needle valve U will prevent a further supply entering the float chamber until some in the chamber has already been used up by the engine. The float chamber having filled to its correct level, the fuel passes along the passages through the diagonal holes in the jet plug Q, when it will be in communication with the main jet P and the pilot feed hole K; the level in these jets being, obviously, the same as that maintained in the float chamber.

Imagine the throttle valve B very slightly open As the piston descends, a partial vacuum is created in the carburettor, causing a rush of air through the pilot air hole L and drawing fuel from the pilot jet J. The mixture of air and fuel is admitted to the engine through the pilot outlet M.

This carburettor was fitted to the whole of the 1930 and all except S8, SB8, SB6 of the 1931 A.J.S. range and replaced the Binks model. These three machines had the new Bowden carburettor. The manufacturers of Amac, B and B, Binks carburettors have now amalgamated, and the Amal carburettor is their latest achievement. For 1932 the Amal instrument is fitted to all models, although some early 1932 T8, TB8, T6 models had the Bowden carburettor. Except in the case of Model T5, the clip fixing shown is replaced by a flanged fixing. All 1933 machines will have the Amal instrument.

The throttle stop is not shown in the above view

The quantity of mixture capable of being passed by the pilot outlet M is insufficient to run the engine. This mixture also carries excess of fuel. Consequently, before a combustible mixture is admitted, throttle valve B must be slightly raised, admitting a further supply of air from the main air intake. The farther the throttle valve is opened, the less will be the depression on the outlet M, but, in turn, a higher depression will be created on the by-pass N, and the pilot mixture will flow from this passage as well as from the outlet M. As the throttle valve is opened farther the fuel passes the main jet P, and this jet governs the mixture strength from seven- eighths to full throttle. For intermediate throttle positions the taper needle C working in the needle jet O is the governing factor. The farther the throttle valve is lifted, the greater the quantity of air admitted to the engine, and a suitable graduation of fuel supply is maintained by means of the taper needle. The air valve D, which is cable-operated on the two-lever carburettor, has the effect of obstructing the main throughway, and, in consequence, increasing the depression on the main jet, enriching the mixture. An accelerating pump unit may be fitted if desired.

The Bowden Carburettor (fitted to some 1931-32 models). This carburettor, introduced for the first time last year on three of the A.J.S. range, is an entirely different design from the Amal carburettor just described. Besides having a butterfly valve instead of a throttle slide, it has a completely automatic action. Although two controls are provided, the twist-grip throttle control is the only one required to be used while driving. The second control (the mixture control) is opened only for starting purposes. Thus manipulation of an air lever while negotiating traffic is not necessary, with consequent low petrol consumption, absence of sooting up of plugs and general efficiency, the mixture being correct under all conditions.

If desired, an accelerating pump unit can easily be fitted to the Bowden carburettor. It is an excellent extra obtainable from the manufacturers, and provides ultra-rapid acceleration without supplying excessive fuel to the engine. Hints on tuning the Bowden carburettor will be found on page 131. The principle of the carburettor is as follows.

Automatic action of the carburettor is obtained by means of a submerged jet, combined with two air injections in series, taking place at different engine speeds. Most people realize that a calibrated jet subjected to a variable suction, will not, under varying conditions of depression, deliver a proportionate weight of petrol to the weight of air passing through the choke tube. If, for example, such an arrangement is used to provide a correct mixture at medium engine revolutions, the mixture supplied at higher engine revolutions will be much too rich. This is corrected by an air injection which reduces the flow of petrol through the jet, and prevents it from increasing too quickly in relation to engine speed. However, above a certain speed, the mixture has a tendency to become rather rich again, and the single air injection is no longer effective.

In the Bowden carburettor, a second air injection is provided which works in series with the. first one. The various means of adjustments for tuning on the Bowden carburettor, ensure that if can be made automatic for any particular engine. Special devices and adjustments are provided to ensure easy starting, slow running, and rapid acceleration.

Figs. 37, 38 show sectional views of the Bowden carburettor from which its general design may be understood. With the engine stopped, the petrol coming from the float chamber passes through the total jet F. By the holes D it reaches the pilot jot G, and through the hole E, fills up the pilot jet well. In the illustration it will be seen that the petrol goes info the full jet A, passing through the main jet B, which is the power jet of the carburettor. The pilot jet G is therefore slightly above the petrol level; the main jet B is under this level, together with the total jet F. These two jets are called submerged jets.

In addition, and independently to the two principal air intakes through the choke tube and venture (air guide), three other small air intakes are provided at different points in the carburettor; at P, where the intake is regulated by a needle valve, controlled by a lever on the handle bar; at N, an air intake for slow running, adjustable by means of a screw M. A third intake is provided underneath the slow running intake, and by a suitable channel air is brought to the pilot jet well K.

Referring to Figs. 37 and 38, let us see exactly how the Bowden carburettor functions. When starting the engine, the butterfly being almost closed, the suction on the full jet A is negligible. The channel delivering the mixture for slow running comes out at the edge of the butterfly, causing very great suction on the pilot jet G. This suction can be increased by closing, partly or fully, the air intake at P, by means of the mixture control lever, in the case of the starting of an engine from cold.

For slow running, the pilot jet G delivers the petrol, which is atomized by the air coming from the intakes N and P. The mixture thus formed passes to the butterfly, where it is mixed with an additional quantity of air, regulated by the opening of the butterfly, and is then delivered to the cylinder.

Page 85

As the butterfly is gradually opened, the suction on the full jet A becomes stronger. This jet delivers petrol, and as air enters into the pilot jet well K, through the suitable channel, the petrol level in this well falls down until the duct communicating with the annular passage C is fully uncovered. At this moment the submerged main jet B delivers petrol into full jet A, and to prevent an increase of this delivery with the increase of the engine speed, if is corrected by a first air injection passing through the suitable channel into K and C. When the throttle is fully opened, the remaining petrol contained in the pilot jet well K and inside the pilot jet G is drawn through holes E and D, allowing the air to pass through the same holes, when it becomes mixed with the petrol delivered by total jet F. The result is a fine emulsion of petrol and air, made possible by this new air injection.

On 1931-33 'T' models the general principles of the system and details are different (see Figs. 10, 22, 40), the pilgrim pump being situated differently, and the oil being fed to the timing side of the crankshaft instead of the driving side and not Kept in constant circulation between the engine and tank

At high engine speeds the submerged total jet F is subjected to a first air injection through D. The petrol and air emulsion passes through the main jet B, when a second air injection takes place in the annular passage C. The petrol mixture delivered by full jet A has therefore been subjected to two air injections in series. It is then finely emulsionized. This emulsion is finally diffused in the main air current coming through the venture and choke tube before it passes into the cylinder. Acceleration at small throttle openings is ensured by the reserve of petrol contained in well A C . This petrol is rapidly drawn into the cylinder when the throttle is opened quickly.

Page 86

1926-28 Mechanical Lubrication System. Prior to 1929 it was the practice for the A.J.S. concern to fit to all production models an engine lubrication system, comprising a Pilgrim mechanical pump (see page 37), gravity-fed from the oil compartment of the tank, and an auxiliary spring-loaded hand pump, or in some cases a hand pump only. This system has worked fairly well, but its day is now definitely past. During the past three years a new an infinitely better system of mechanical lubrication has been evolved and perfected by the experimental and research department. The first machines fitted with this system were overhead valve racing machines, and these, later on, were followed by the O.H.V, standard models. Various races were entered, including the T.T. races, and the functioning of the lubrication carefully noted, and various minor defects afterwards remedied, with the result that to-day it is almost perfect after a few initial disappointments, and is standardized on all models except the 1933 camshafts and big twins. The main oil supply is now capable of adjustment by a control knob.

Page 87

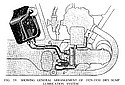

The 1929 30 Dry Sump System. This is shown diagrammatically in fig. 39, while Fig. 41 shows how the oil circulates. The essential difference between the dry sump system and other methods is that in the former case a large quantify of oil is in continuous circulation throughout the engine and tank, while in the latter case only a comparatively small volume of oil at any given time is circulating. Chief among the advantages accruing to the D.S. system are the following: (a) No attention is required by the rider other than maintaining the oil in the separate tank mounted on the rear down tube at the correct level, (b) Superior cooling of the engine lubricant is obtained, (c) Simple means for filtering the oil and preventing the rapid accumulation of pulverized carbon deposits can be provided, (d) There is no possibility of the engine being greatly over-oiled since the sump remains practically 'dry,' all superfluous oil being returned to the tank by the duplex pump, (e) Oil consumption remains remarkably low, due to a minimum of leakage or combustion taking place. So much, then, regarding the merits of the system. We will now inquire into the construction and working of the 1930 system.

The "heart" of the circulation system is the duplex pump D driven by a simple coupling from the inlet cam shaft. Lubricating oil from the main tank A is drawn via the pipe C, after passing through the filter B, into the pump itself and thence

projected along pipe E to the near side of the engine. It then passes down through a channel in the crankcase and is forced, under pressure, into the hollow mainshaft (see Fig. 41) along which it travels to the all-important big end roller bearing. This it very thoroughly lubricates as the oil oozes out and drips upon the flywheels which, by centrifugal force, splash it upon the cylinder walls. Oil mist, in fact, penetrates throughout the working parts. Oil is also pressure-fed to the timing case. It should be noted from Fig. 41 that by rotating the needle valve, seen on the left, a few turns, lubricant can be fed direct to the cylinder walls via a by-pass. This, however, is only intended for fast racing work. All lubricating oil, after effecting its purpose, eventually drains to the bottom of the sump, thence to be returned to the pump via the pipe 67 (Fig. 39) after passing the second filter F. Finally, it is forced under pressure up the pipe H and back into the tank again to be recirculated ad infinitum.

Page 88

1931-33 Improved Mechanical Lubrication. All 1931 to 1933 engines, except the 33/2 models and "camshafts," incorporate a lubrication system quite different from the 1930 system in principle as well as design. The oil in the tank is not kept in constant circulation, and the duplex Pilgrim pump (Fig. 22) is driven from the crankshaft. The upper plunger sucks oil from the tank via the delivery pipe, and delivers if direct to a false bearing on the timing side, not the driving side, of the crankshaft. The oil-way is totally enclosed, no pipe being used as on the 1930 system. The oil is then pressure-fed to the big end bearing, as shown in Fig. 40. Some of if is also forced to the timing gear. Surplus oil drops down from the big end on to the flywheels and is distributed by splash throughout the engine. The lower pump plunger collects some oil from a by-pass from the main feed and returns it to the tank via the return pipe, from whose orifice oil may be seen emerging on removing the filler cap. There is no separate oil feed to the cylinder walls as on the D.S. system, but the main supply can now be controlled by means of the regulator on top of the pump, illustrated on page 37. The oil return to the tank only shows that the pump is working.

Page 89

The Dry Sump Lubrication System (Big Twins). The lubrication system for 1933 does not apply to 1931 or the 'camshaft' models. It is of the force-feed, constant circulation type with dry sump. Briefly its working is as follows: Oil is sucked from the tank, distributed throughout the engine, and finally returned to the tank by a duplex internal pump. This comprises a single doubleacting, steel plunger (Fig. 41 A), housed in the crankcase casting below the timing case between two rectangular end caps horizontally and at right angles to the crankshaft axis, and able simultaneously to rotate and reciprocate. This dual action of the plunger is obtained, as is more fully explained on page 90, by the fact that while a, positive rotation at one-fifteenth engine speed is effected by direct engagement of a central hubbed portion with a. worm cut on the mainshaft, an endwise movement is secured by having an annular cam groove cut in the plunger body in permanent contact with the hardened end of a fixed guide screw. The actual oil circulation is brought about by alternate displacements and suctions of the two ends of the reciprocating plunger, one end being of greater diameter than the other to ensure complete scavenging of the sump and the return of all surplus oil to the tank. Two segments cut in the plunger body constitute the main ports which regulate the circulation. There is no adjustment however. A point worthy of notice here is that the crankcase cannot safely be split until the pump plunger has first been removed.

With regard to the actual oil distribution, the system adopted is made clear by reference to Fig. 41 A. The small end of the plunger (i.e. the front one) forces oil up into the timing case to a predetermined level, such that the camshaft bearings and drive are adequately lubricated. All surplus oil overflows into the flywheel chamber, and is eventually returned to the sump, although some of it is caught up by the flywheels and splashed upon the big-ends and the cylinders. Splash lubrication, however, is not relied upon to any extent owing to the small volume of oil remaining at any time in the sump. Oil is forced under pressure direct to the big-end bearings and to the crankshaft bearing on the timing side by means of carefully drilled passages in the flywheel and mainshaft concerned, respectively. Oil is also fed to three points on each of the cylinder walls in such a position that the bulk of the oil is discharged on to that part of the thrust side of the cylinder walls where the maximum cooling effect upon the pistons is required.

The constant circulation system with fabric filter (see page 22) guarantees a continual supply of clean, cool oil to the engine whenever the latter is running. The oil circulation may be verified occasionally by removing the oil tank filler cap and noting whether oil is being ejected from the return pipe orifice. This check upon the oil circulation should be made preferably upon starting up the engine from cold. Remember the fact that when the engine has been left stationary for some time, oil from various parts of the engine has drained to the sump, and, until this surplus has been cleared, the return to the tank is very positive, whereas normally it is somewhat spasmodic and, perhaps, mixed with air bubbles, due partly to the fact that the capacity of the return part of the pump is greater than that of the delivery portion, and partly to the (act that there are considerable variations in the amount of oil held in suspense in the crankcase. For example, upon suddenly accelerating, the return flow may decrease entirely for a time only, of course, to resume at a greater rate than before when decelerating. If may be mentioned, however, that on all Big Twin models the provision of a. tell-tale on the instrument panel, illuminated at night, obviates the necessity for removing the filler cap, the oil supply to the timing- box being first by-passed up to the panel. It is important that no air leaks occur in this system.

Page 90

The Double-acting Oil Pump. A general description of the 33/2 dry sump lubrication system has already been given, and Fig. 41A shows how the oil is circulated. It remains to deal with the action of the pump itself. As already mentioned on page 89, the pump has only one moving part a steel plunger driven at 1/15 engine speed by a worm cut on the engine mainshaft. This plunger slowly oscillates to and fro, its precise travel being determined by the relieved end of a guide screw (b. Fig. 41 A) screwed into the rear of the pump housing and engaging with a profiled cam groove at the large return end of the plunger. This groove plays an all important part. In addition to causing the plunger to oscillate and thereby obtain a pumping action at each end (for the plunger is completely enclosed by its housing and end caps), its carefully planned contour enables the pumping impulses to be synchronized with the opening and closing of two main ports and a small auxiliary port, thus definitely regulating the oil circulation and controlling the supply of oil to the engine and the return of oil to the tank.

The two main ports are shown at D and C, and the small auxiliary port at E, Fig. 41 A. The main ports are known as the delivery port and the return port respectively. They comprise two shallow segments cut in the pump plunger body and communicating with the hollowed ends of the plunger by two holes. The auxiliary port comprises simply an 1/8 in. diameter hole drilled at the back of the main delivery port segment. The plunger itself, as mentioned on page 89, has two diameters, and, therefore, the capacity of the return portion of the pump is greater than that of the delivery portion, so that the sump is always kept clear of oil. Fig. 41A enables the action of the pump to be understood. Oil flows by gravity, assisted by suction, from the tank to a point in the pump housing, such that no further passage can take place until the plunger has moved to a point, approximately, as shown when oil flows into the hollowed end via the cut-away segment constituting the delivery port. Then as the plunger continues to advance with simultaneous reciprocation, the oil which has completely filled the hollowed end is momentarily retained and the bulk of it finally ejected by displacement from this port into an oil passage opposite the point of entry, and forced to the cylinder walls and main engine bearings.

A Hobbed portion of plunger C Plunger return port

B Annular cam groove D Plunger delivery port

b Guide screw (crankcase) F Small auxiliary port

During the advance of the plunger culminating in the automatic injection of fresh oil into the engine, the receding of the large end of the plunger causes a strong vacuum directly opposite an oil passage leading from the sump base, and communicating with the plunger interior only when the return port is in a suitable position. All surplus oil in the sump is, therefore, sucked up as the plunger advances, and retained when the port closes until the plunger begins to reverse its motion, when the return port, corning into line with the return pipe passage, the oil is forcibly ejected by displacement into this pipe, and so to the oil tank, where its intermittent emergence can, though a tell-tale (Fig. 19a) is provided, be observed.

Thus it will be seen, that so long as the engine is running fresh oil is being constantly fed to it and then, after circulation, sucked from the sump and forced up back into the tank to be recirculated ad infinitum. Coincident with the ejection of oil from the main delivery port a supply of oil is forced out of the auxiliary port to the timing box. Since a tell-tale is provided it is first forced up into the panel, whence if flows by gravity to the respective parts requiring lubrication. Only a small portion of the total oil feed to the engine is diverted in this manner, but this portion is important and a definite index as to the correct functioning of the whole D.S. lubrication system, for only when the pump is forcing oil into the engine at a certain pressure can the rise of the tell-tale plunger be observed. The action of the pump plunger is almost, fool-proof, but care must be taken to remove the plunger before separating the crankcase, and the guide screw (b) must always be kept fully tightened. A point worthy of note is that with the plunger stationary no oil can possibly enter the engine.

Page 92: Sturmey-Archer & AJS Gearboxes 1932-33